Rock the Frock- 1620s Spanish Court Gown

Back with #RockTheFrock after several years as I have finally found enough information about one of my favourite styles and item. It’s taken years to work through digitisation and to potentially make a connection between a few different early 20thC costume history books.

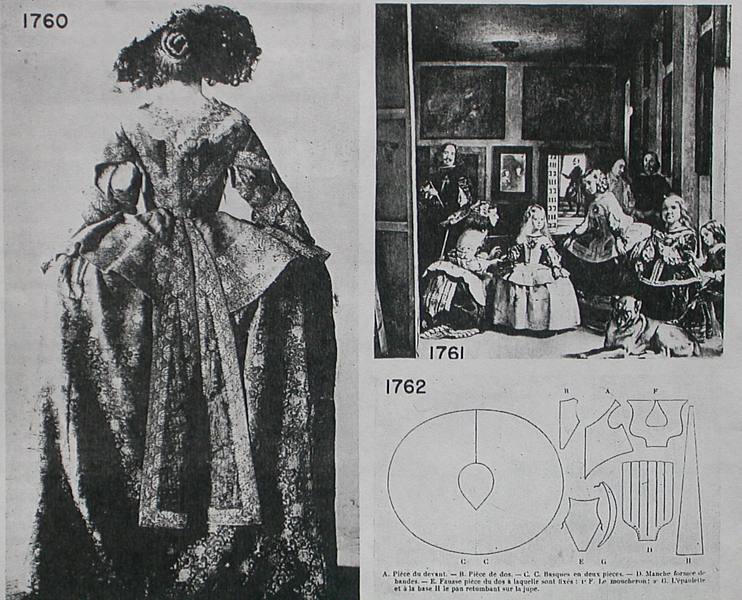

“Mannequin de dos en costume espagnol XVIIe” and “Mannequin en habit à l’espagnole de la collection Worth“

This (was?) is a genuinely extant garment from the “Collection Worth” that was on display for the Société de l’histoire du costume in 1900. A booklet for the society was published in 1907 that included an article by Maurice Leloir: “A propos de la premiere exposition de costumes anciens,” pgs 156-196, Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire du costume, Leroy (Paris).

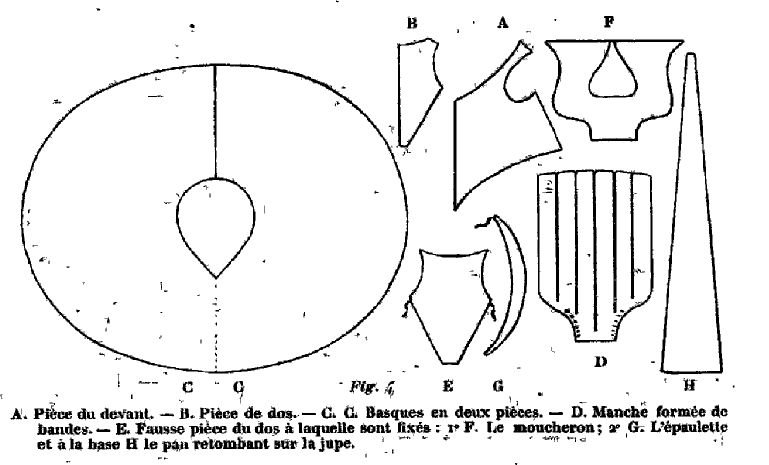

The pattern was also shared in this article on page 161:

If either of these seem familiar, the back view of the mannequin and gown and the pattern are also published in Millia Davenport’s Book of Costume (fig 1760 and 1762.)

I have loved this gown ever since I found that set of figures in Book of Costume but I’ve set it aside as I have not trusted the source- Leloir. There is good news and bad news. It was an extant garment indeed. And was part of the Worth Collection.

It was on loan for the exhibit but was altered.

“Leloir described how the SHC modified and altered a rare seventeenth-century Spanish formal court corset lent by Worth in order to mount it for display”

Fashion Collections, Collectors, and Exhibitions in France, 1874–1900: Historical Imagination, the Spectacular Past, and the Practice of Restoration

Maude Bass-Krueger ORCID Icon

Pages 405-433 | Published online: 31 Jan 2018

https://doi.org/10.1080/1362704X.2018.1425354

Pretty heart breaking, but it gets worse. Bass-Krueger translates the section within the article Leloir wrote:

The corset was such that it produced no effect when put on a mannequin. We had to rip out the used lining and patch the cloth. The parts that were embroidered had been saved by the embroidery itself. But the plain parts, used, in tatters, no longer gave the garment shape. They had been most cut away from the embroidery and replaced quite skillfully from fabric taken from the skirt. That explains why the skirt was missing. In two places, at the underside of the arms, the original fabric remained with its wear and tear. We replaced the skirt, on the mannequin, with fabric that looked analogous in color and in period, loaned to us by M. De Cuvillon. After this work (putting the fabric back between the embroidery), everything had been relined with a new blue silk, and then sewn back together quite well, except for the sleeves. How was it that several embroidered bands around the sleeves had disappeared? The count wasn’t there to redo the two sleeves. We replaced the missing three bands by a painted textile. Thanks to Velasquez’s portraits we were able to reconstitute the garment as it should have been. (Leloir 1909, 159)

Ibid.

I can’t imagine how M. Worth would have felt. I’m devastated at this distance of time and space!

This habit of restoration and transformation was not limited to this garment. Extant garments were shared between collectors and artists and made over to put on models for their own art. Leloir was no exception. It’s possible to compare plates prepared for “Histoire du Costume” with exhibition photos and with his art and find garments and even mannequins.

The clothes sometimes have several different inscriptions which seem to attest to a real circulation of the object between the different actors of this network of collectors. The proliferation of these stamps also raises the question of the use of these garments beyond their collection.

La collection Maurice Leloir et la collection de la Société de l’histoire du costume, Le fonds ancien du Palais Galliera, musée de la Mode de la Ville de Paris : nouvelles perspectives de recherche

Pascale Gorguet-Ballesteros and Marie Bonin

https://books.openedition.org/inha/6915?lang=en

Incredibly though, Leloir gives us a name and clues as to how reproductions were made at the time.

“The joy of Clootens was to imitate the way of the craftsmen of old, in shoes, clothes, lingerie, anything, his pride in having cut, to have sewn like an old man, he said. […] He worked so well, mimicked everything so perfectly that every time I see a piece of costume prior to the18th century in good condition, I am wary and imagine that Clootens has been there”

Ibid.

This might explain a handful of garments photographed for other costume history books at the same time. The later book by Karl Kohler has a handful of suspect garments, though some are simply poorly mounted. But possibly also in Dress Design by Talbot Hughes.

Fortunately most of the very rare and older garments seem to have been barely supported so that we can recognise at least three surcoats that have since been patterned by Janet Arnold:

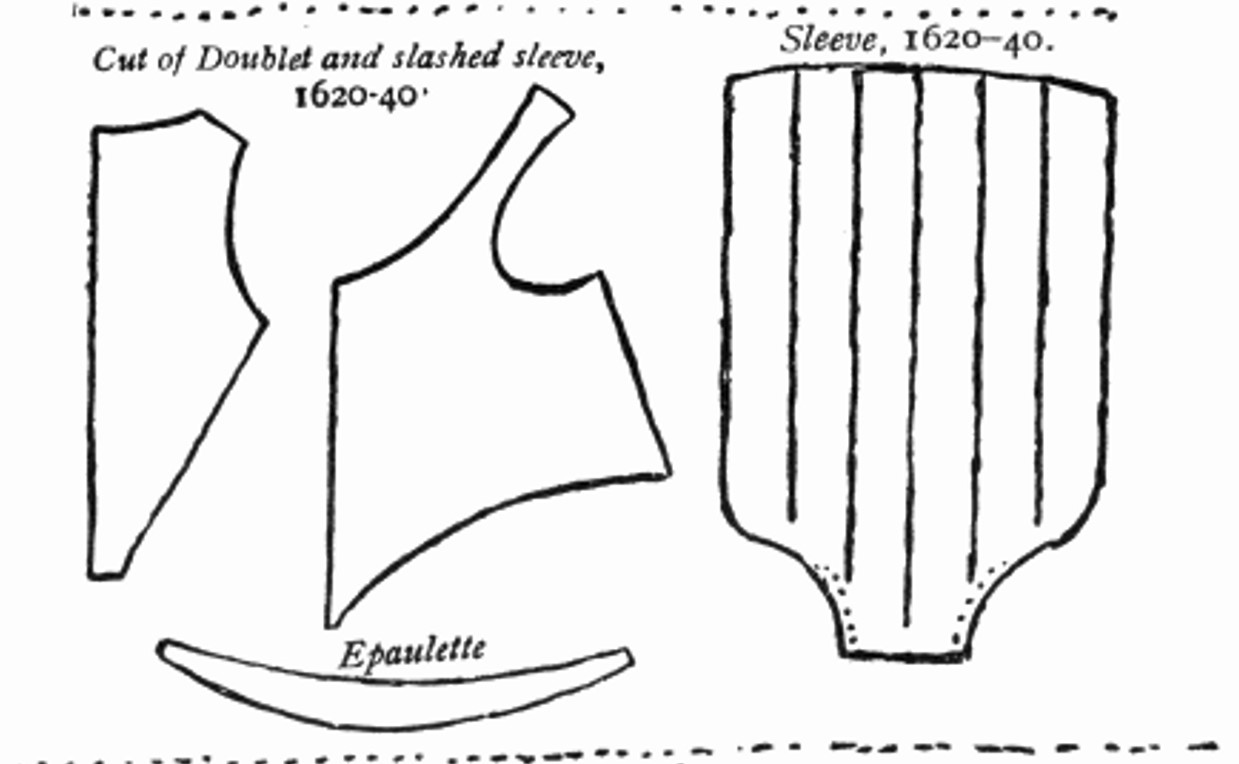

However There is a curious pattern in the middle of pattern 67, The pattern states it is a doublet, but the text states “Bodice with slashed sleeve, 1620-40” and it is very familiar indeed:

This is nearly exact to the Leloir diagram. Both Davenport and Hughes seem to have had access to this pattern. As there is no fully digitised copy of Leloir’s “Histoire du Costume” I can’t tell if he published this pattern and gown in that work as well. But it does go to how influential the Société de l’histoire du costume and Leloir were.